ADVERTISEMENT

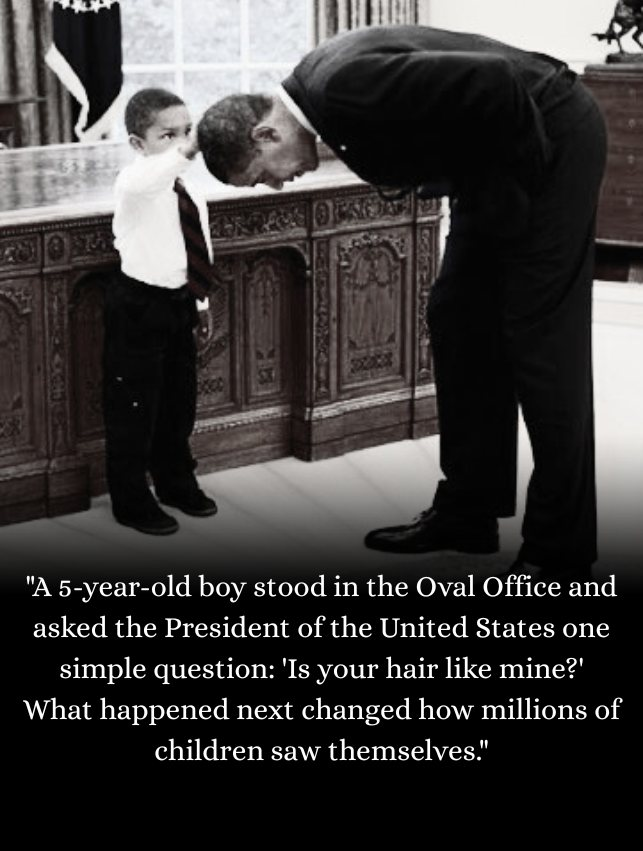

“I want you to think of that little Black boy in the Oval Office touching the head of the first Black President,” she told audiences. The image symbolized the progress African Americans had fought for across generations. Not just political progress. Personal progress. The kind that happens inside a child’s understanding of who he might become.

The photo became iconic not because it showed power, but because it showed possibility. It captured the moment when the extraordinary became familiar. When the highest office in America bent down to eye level with a child and said: Yes. You belong here too.

For generations, that had been unimaginable. Black children grew up seeing presidents who looked nothing like them. The presidency existed in a world that didn’t include them—not as participants, not as leaders, not as people who could stand in that room and feel at home.

Jacob’s question revealed what representation does for children. It transforms abstract possibility into concrete reality. It turns “maybe someday for someone” into “right now for me.”

Children don’t process belonging through policy speeches or historic firsts. They process it through small details. Hair texture. Skin tone. The way someone stands. A sense of being seen and recognized in the most ordinary, intimate ways.

Jacob wasn’t asking about civil rights history. He was asking: Are you like me? Can I see myself in you?

And when Obama said yes—when he bowed his head and let Jacob confirm it through touch—he answered a question that millions of children had been asking without words for their entire lives.

President Obama later reflected on why that photograph mattered so much to him.

“I think this picture embodied one of the hopes that I had when I first started running for office,” he said. “If I were to win, young people—particularly African American people, people of color, outsiders, folks who maybe didn’t always feel like they belonged—they’d look at themselves differently.”

He understood that seeing someone who looks like you in positions of power doesn’t just change opportunities. It changes imagination. It changes what children believe about themselves before they’re old enough to articulate those beliefs.

Jacob’s father, Carlton, put it simply: “It’s important for Black children to see a Black man as president. You can believe that any position is possible if you see a Black person in it.”

The photograph lived beyond that administration. It hung in the West Wing throughout Obama’s presidency. It became part of the permanent collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

And thirteen years later, in 2022, it came full circle.

Jacob Philadelphia was eighteen, about to graduate high school. He planned to study political science at the University of Memphis.

President Obama reached out. He wanted to congratulate Jacob on his graduation.

They connected by video call. Obama on screen in his Washington office, where that photograph still hangs. Jacob looking back at him from Uganda, no longer the small boy with the quiet question but a young man shaped, in part, by the answer he received that day.

“Do you remember me?” Obama asked, smiling.

Continue reading…

Continue READING

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT